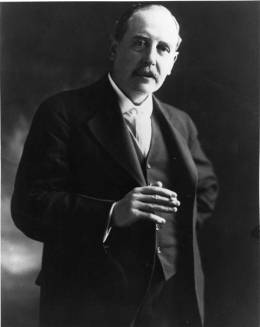

Edwin Henry Lemare

(1865-1934)

The Popular Organist

A Brief Overview of the Life and Legacy of Edwin H. Lemare

By Jonathan Gradin

Edwin Henry Lemare

(1865-1934)

Edwin H. Lemare was a world-famous organist, composer and transcriber of orchestral works for the organ, and was often regarded as the greatest living organist of his time.

Born Sept. 9, 1865 in Ventnor, on England's Isle of Wight, the young Lemare took choral and organ lessons at Holy Trinity Church from his father, also named Edwin. Many of the young Lemare's relatives were organists, so this might have had some effect on his musical inclinations.

Lemare started composing piano music at age five, and by age six had played his first recital. His father bought him a small reed organ, putting him, in his own words, in seventh heaven. By age 12 he had become a very proficient pianist; however, he decided to make the organ his main instrument, as it suited his Romantic/orchestral musical style.

In 1878, at the young age of 13, Lemare was awarded a three-year scholarship to study at the Royal Academy of Music. During his time there he studied piano and organ under the likes of Sir G.A. MacFarren, Walter C. MacFarren, Dr Charles Steggall and Dr Edmund H. Turpin.

The 19-year-old Lemare got a great deal of fame playing over 140 recitals—two a day—at London's Inventions Exhibition of 1884. The organ was a small one-manual Brindley & Foster organ, on which Lemare amazed people, making the organ “dance.”

In 1886 Lemare gave bi-weekly recitals on the Willis organ in Park Hall, Cardiff, for a period of five months, using this as a stepping-stone to more prestigious positions, such as Sheffield Parish Church and Sheffield’s Albert Hall. That same year, at age 20, he received the F.R.C.O.—Fellowship of the Royal College of Organists—a prestigious award, especially for a man that young.

While in Sheffield, he met and fell in love with a young lady named Marian Broomhead Colton-Fox, the daughter of a well-known attorney; they eloped in 1892 because her father disapproved of Lemare. Little else is known about their relationship; however, Marian was a shy lady, and was dealt a great blow when her father was killed in a train accident one-and-a-half years later.

From this point on, however, Lemare's fame skyrocketed. In 1892, he accepted a position at Holy Trinity Church in London and became an organ professor and examiner for the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. This move to London helped his popularity immensely; the large populace as well as the means to advertise offered many opportunities for advancement.

In 1894 Lemare, his wife and some friends went to Bayreuth, Germany for the Wagner festival, hearing many of Wagner's works in a marathon of sorts. Here he got the permission of Wagner's widow, Cosima, to perform the first act of Parsifal outside of Bayreuth for the first time; he performed this on March 1, 1898.

One such opportunity came in 1897, when he—following his good friend, the Rev. Robert Eyton—became organist at St. Margaret’s, a sizeable church with an organ that fitted Lemare’s style. Here, Lemare played concert-quality services, which had people lined up around the block! He would also host special concerts there, including his famous March 1, 1898 performance of the first act of Wagner’s Opera Parsifal; he performed straight from the orchestral score. All the newspapers carried rave reviews of that concert. Even Felix Mottl, one of the original conductors of Wagner’s opera at Bayreuth, praised Lemare, saying:

I would not have thought the organ capable of producing in such detail the effects of the full orchestra . . . I have nothing to say except beautiful, beautiful.

In January 1899, the Rev. Robert Eyton, who had been a firm supporter of Lemare's music, resigned from St. Margaret's. The new rector, Rev. Herbert Henley Henson, was not prepared for, nor supportive of, Lemare's concert-like playing. Lemare normally did a lengthy improvisation during the offertory; therefore, on Henson's first Sunday, he played Eternal Father, Strong to Save, launching into a tone-poem depicting a ferocious naval battle and aftermath. Henson flipped his lid, drastically cutting back the music funding.

At around this same time, Lemare's relationship with Marian strained to the breaking point; the divorce was finalized in April 1900. Shortly thereafter he married Elsie Francis Reith, a clergyman's daughter.

After Christmas that same year, Lemare, sensing his usefulness at St. Margaret's was ending, took a 100-recital tour of the U.S. and Canada, lasting into 1901; he played many great organs there, leaving him with a good impression and potential job opportunities. He left St. Margaret’s in 1902, accepting a contract with the Carnegie institute in Pittsburgh; from that point on he lived in North America. He was paid $4,000 a year; this was five times more than his salary at the Church.

When the Lemares were on a trip to England, his wife had a daughter, Iris, on September 27 1902. He was in Sheffield playing a special concert Albert Hall, on the instrument that he had played many years before, at the start of his career.

Lemare stayed with the Carnegie Institute until 1905. During and after this time he concentrated on concert tours and special engagements, such as his August 1908 engagement at Ocean Grove, playing their new Hope-Jones organ. In 1903 and 1906 he went on concert tours in Australia and New Zealand, playing at the Melbourne Town Hall, Auckland Town Hall and Sydney Town Hall, which was in such a bad condition that Lemare took a two-week stretch to get it restored and working properly. He acted as designer and advisor on the construction of the organs in Melbourne and Auckland; he designed the former to replace the old William Hill organ, which was in need of a full rebuilding and, in Lemare’s eyes, unsatisfactory, both tonally and mechanically. The city council’s report echoed this sentiment; consequently, the organ was rebuilt, revoiced and expanded, with a new console incorporating all the latest features made possible by the new electro-pneumatic action, which Lemare heartily endorsed.

In the years leading up to 1909, Mrs. Lemare's health was failing, and Mr. Lemare couldn't let her get in the way of his career. He filed for divorce that year; this had a mild effect on his career, but he quickly rebounded. Two weeks later, he married Charlotte Bauersmith, a young organist and fan from Pittsburgh with who had been a friend of his for years.

By 1910, the 44-year-old Lemare reached the zenith of his career, going on concert tours across the States as well as in England, where an aspiring young organist named E. Power Biggs heard the great master at work. Lemare spent the summer of 1911 arranging and composing new works for the organ. He was always in demand, filling houses wherever he went; consequently, the strain caught up with him, and he would often be on the verge of falling asleep. This same year, his wife, Charlotte, had a son; they named him Edwin Lemare III, who from a young age traveled the world with his parents.

In 1913, there was an opening for the post of organist at St. George's Hall, Liverpool. Many people wanted Lemare to assume that position; however, the town council gave the post to another organist. Lemare was not without options; he was booked solid with concerts in other parts of England.

Later that year Lemare went to Germany to record 96 Welte player organ rolls, which are the only recordings that give a fair approximation of his playing skill; his four songs recorded on 78s in 1927 don’t show his full potential, as they were recorded on a small organ unsuited for his music.

In 1915, Charlotte Lemare gave birth to a second child in England, this time a girl: Betty Ellison Lemare. Due to the ongoing war, sea travel was limited, making Lemare late for his most important booking yet: San Francisco's Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

On Feb. 21, 1915, the Exposition opened in San Francisco featuring, among other things, a large Austin pipe organ in 4000-seat Festival Hall. Out of at least 48 leading recitalists giving daily performances, Lemare was the most famous. Although his first recital—in August—attracted only 400 people, as word spread of the ‘new kid on the block,’ the hall was filled to capacity every time! In fact, Fair officials approved the expansion of Festival Hall because Lemare actually made money for them. By the time the fair closed in December, Lemare had played 121 concerts, with almost 150,000 people having heard him.

Unusually, the fair turned a profit; consequently, the Exposition Company donated the profits to the City, with the intent of transferring the organ to a permanent location in the newly constructed Civic Auditorium. Lemare was hired to oversee the reinstallation and revoicing of the organ, as well as being hired on as San Francisco’s first Municipal Organist; he was under contract to play two concerts a week. His salary was $10,000 a year, making him one of the highest-paid organists in the world. In November 1920, the voters approved a reduction of his salary to $3,600 a year; consequently, he quit, giving his 190th and last concert on June 26, 1921.

After this he went across the country to Portland, Maine, where he played the Kotzschmar Memorial Organ in the City Hall Auditorium, now called Merrill Auditorium. He stayed there for around two years, leaving in 1924 to supervise the design of Chattanooga’s new municipal organ.

In 1925 Lemare accepted the post of municipal organist there, playing the new four-manual Austin—designed to Lemare’s specification—in the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Auditorium. Lemare gave his premiere there on Feb. 12, 1925, opening with the Star-Spangled Banner; 4,000 people attended that event.

Lemare gave weekly concerts on Sunday from October to June. One problem he found was that to keep his audience, which was mostly made up of simple folk, he had to use a lot of popular tunes, simple songs like Pop Goes the Weasel, Dixie and Swanee River. In spite of this, he managed to draw record crowds five years in a row, educating them in the process. His contract, however, expired at the end of May 1929.

By this time Lemare began to be overshadowed by a young man named Marcel Dupre, who would go on to great fame as a symphonic organist and composer. Lemare was getting old, and he realized that the mantle must be passed on to the younger generation. He then retired to Hollywood, California, until, five years later—on Sept. 24, 1934—he died of a series of heart attacks. He had just turned 69, having lived half his life in the 19th century and the other half in the 20th. He was buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. The stock market crash and ensuing depression had wiped out his entire life savings, leaving him penniless with no inheritance.

The world’s most popular organist died virtually forgotten. The advent of higher-fidelity recordings somewhat obviated the need, in the public’s mind, for municipal organists and orchestral transcriptions. Also, currents were changing in the academic organ community. The pendulum was swinging back to baroque ideals, which were the antithesis of the symphonic organ ideal. Lemare—and many great organs of that time period—became victims of the changing tide; consequently, many of his works were forgotten until the 1980s, when the symphonic organ came to be accepted as works of art, representative of that unique era.

There were several reasons for Lemare’s popularity in life.

First, his technical genius and ability amazed people. Lemare perfected the art of thumbing, which had been used by his predecessor and source of inspiration, W.T. Best. Thumbing is a technique that allows a player to play a melody line and accompaniment simultaneously on two manuals, with just one hand. Lemare could, on a four-manual organ, play two melody lines with his right hand, two separate ones with his left, one on the pedals with his right foot and the bass line with his left. This technique came in handy when transcribing large, complex orchestral works, as it allowed him to maintain the separation of orchestral parts when necessary.

Lemare was adept at producing orchestral registrations, smooth stop changes and attack and phrasing effects, which had previously been unattainable. Lemare was able to simulate these effects partly because of the invention and widespread adoption of balanced swell pedals, which, unlike the previous designs, stay open at whatever position the organist leaves them in, allowing for almost infinite possibilities for expressing the melody. The trend towards the symphonic organ sound in the late 1800s and early 1900s went hand-in-hand with Lemare’s philosophy of the role of the organ. Sir Malcolm Sargent, the famous English composer, said, “Lemare did something I never thought possible. He made the organ dance.”

His earlier piano training helped him immensely in this symphonic style, both in fingering and his staccato and rubato effects, which were noticeably absent from other organists' playing.

Lemare believed that the organ's proper place was as a solo instrument, upon which almost any music could be played. He also saw it as a way to bring quality music to the masses; orchestras were too expensive for many towns, and the common people could not afford to attend the concerts. An organ recital was inexpensive because there was only one performer to pay, rather than a large symphony.

Lemare felt that in order to be recognized as an ‘artistic instrument,’ the organ had to be ‘properly built and properly played.’ This meant not only raising the standards of organ-building, a passion Lemare shared with George Ashdown Audsley, but also, and arguably more important, raising the standard of playing, through education and certification.

Lemare saw the organ, especially the modern designs being built, as the perfect tool for the masses to hear the latest orchestral works, as well as the literature. His belief in this concept is evident in his concert programming, which regularly featured four major types of music.

First, he tried to feature at least one work by J.S. Bach, who was relatively unknown to organ audiences. Lemare, in true Romantic fashion, played Bach with expression and nuance, making the music come alive. Typically, he would play a virtuoso piece, such as the ‘Gigue’ Fugue in G major (BWV 577) or the Prelude and Fugue in D major (BWV 532); however, sometimes he would play the Prelude in B minor (BWV 544), substituting the conventional Full Organ registration with soft strings, bringing out the melody in a haunting, emotional fashion.

Lemare, primarily early on in his career, played many Romantic organ works by such composers as Felix Mendelssohn, Charles-Marie Widor, Rheinberger, Guilmant, and others, helping to spread their popularity to the masses. In later years, however, he tended to feature his own compositions, which were in that same style.

A big part of Lemare’s popularity was due to his ability to simultaneously improvise on several themes submitted to him by the audience; consequently, this played somewhat of a major role in his concerts. Usually he would do his improvisations near the end, keeping the audience’s attention from fading.

Transcriptions were possibly the most important part of Lemare’s repertoire, with good reason. In his mind there simply was not enough literature from the Romantic era to do a literature-only concert; also, the average audience would get bored rather quickly. Transcriptions fulfilled Lemare’s previous mentioned concept of the organ as a means to bring music to the masses. In addition to orchestral and operatic works, Lemare transcribed a great deal of familiar folk songs and other tunes for the organ. These pieces, while maybe not as ‘good’ as the ‘serious’ music, would be popular with the crowds; therefore, they might be attracted to attend more concerts and, at the same time, hear the serious music.

This aspect of tailoring a performance to please the masses in this way has been lacking during the last 40 years because the purist academia started to look down upon such practices; consequently, recital attendance is next to nil in many places. Hopefully, though, the tide is changing with the new generation of organists.

Brief mention has been made of Lemare’s organ music, both original and transcriptions. He was a prolific composer, having published over 50 original organ compositions, at least 158 transcriptions of all types, church music, even an orchestral symphony.

One of Lemare’s most famous original pieces is his Andantino in D flat, although most would not recognize it under that title. American songwriters Ben Black and Charles N. Daniels added—without Lemare’s permission—words, forming the hit song Moonlight and Roses. Lemare received a share of the royalties after threatening legal action. Another famous piece is his Caprice Orientale (Op. 46), which uses a rhythmic pattern reminiscent of a Spanish dance.

Lemare’s biggest legacy is his organ transcriptions. These are some of the hardest transcriptions ever published, but they are arguably the closest to the intent of the original orchestral score.

These transcriptions ranged from Wagner (25 works transcribed) to Elgar and Brahms. The transcriptions included opera excerpts, traditional songs, orchestral and chamber pieces, even a surprising amount of piano music. A breakdown of his transcriptions by composer, genre and period can be found on the Performance Online website: www.performanceonline.org, in an article by Sverker Jullander.

A great many of these pieces have been recorded on CDs in recent years. Frederick Hohman has recorded his Lemare Affair series of CDs on the Pro Organo label (www.proorgano.com). These are also available through the Organ Historical Society catalog (www.ohscatalog.org).

All of Lemare's known printed organ works have been republished by Wayne Leupold Editions in two series: Original Compositions and Transcriptions; these are available online at www.wayneleupold.com, for the brave soul who dares to master them.

Special credit belongs to Nelson Barden, who has researched Lemare extensively; Frederick Hohman, for information on his Lemare Affair CDs; Vic Ferrer, For information relating to the San Francisco Exhibition; and last but not least, the members of PIPORG-l and Pipechat for assisting me with links, information, and contacts.

Bibliography

Barden, Nelson. Edwin H. Lemare. Published in The American Organist Magazine, January, March, June and August 1986.

Edwin H. Lemare page. ACCHOS website. http://www.acchos.org/html/links_edwin_lemare.html

Edwin H. Lemare. Chattanooga AGO website. http://www.agochattanooga.org/chattanoogaaustin/pages/Lemare.htm

Edwin H. Lemare Wikipedia Article. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_H._Lemare

Ferrer, Vic. Behind the Velvet Curtain info page. http://vicferrerproductions.com/docum/velvet_curtain/index.html

Hohman, Frederick. Lemare Affair. Pro Organo CD 7007. Copyright Zarex Corp. www.zarex.com

Jullander, Sverker. Transcription as the Performer’s Strategic Tool: The Case of Edwin Lemare and the Organ. Performance Online. http://www.nunomartino.com/performanceonline/Jullander_uk.pdf

Municipal Organs Website. http://www.municipalorgans.net/Lemare.htm

OCA Feature Article Melbourne Town Hall Organ. http://www.hillwoodrecordings.com/OCA32001Feature6.html

Whitney, Craig R. All the Stops: The Glorious Pipe Organ and Its American Masters. New York: Public Affairs 2003.