The Museum Of Yesterday presents...

LIFE IN THE MID- 20th CENTURY AMERICAN HOME

LIFE IN THE MID- 20th CENTURY AMERICAN HOME

|

The photo above illustrates what was a typical American living room in the immediate post World War II era. The Bendix table radio, upholstered chair, and wool rug were typical of living rooms of that era. The "middle-class" American home was evolving, having come a long way from its origins as the strictly utilitarian shelter of the early 1800s. By 1940, "Decor" had become increasingly important, and the family of the 1930s and 1940s had come to expect comforts such as radio, upholstered furniture, finished rooms, and ornamentation, that had not been seen in any but the most lavish homes of the prior era. This portion of our exhibit serves to illustrate the development of both decor and technology in the home, beginning with upscale homes of the late 1800s through the great era of American productivity that was Post-World War II America. The average life expectancy for men was 47 years. Fuel for cars was sold in drug stores only. Only 14 percent of the homes had a bathtub. Only 8 percent of the homes had a telephone. There were only 8,000 cars and only 144 miles of paved roads. The maximum speed limit in most cities was 10 mph. The tallest structure in the world was the Eiffel Tower! The average US wage in 1910 was 22 cents per hour. The average US worker made between $200 and $400 per year. A competent accountant could expect to earn $2,000 per year, a dentist $2,500 per year, a veterinarian between $1,500 and $4,000 per year, and a mechanical engineer about $5,000 per year. More than 95 percent of all births took place at HOME. Ninety percent of all Physicians had NO COLLEGE EDUCATION! Instead, they attended so-called medical schools, many of which were condemned in the press AND the government as 'substandard.' Sugar cost four cents a pound. Eggs were fourteen cents a dozen. Coffee was fifteen cents a pound. Most women only washed their hair once a month, and used Borax or egg yolks for shampoo. Canada passed a law that prohibited poor people from entering into their country for any reason. The five leading causes of death were: 1. Pneumonia and influenza, 2. Tuberculosis, 3. Diarrhea, 4. Heart disease, 5. Stroke The American flag had 45 stars. The population of Las Vegas Nevada was only 30! Crossword puzzles, canned beer, and iced tea hadn't been invented yet. There was no Mother's Day or Father's Day. Two out of every 10 adults couldn't read or write and only 6 percent of all Americans had graduated from high school. Eighteen percent of households had at least one full-time servant or domestic help. There were about 230 reported murders in the ENTIRE U.S.A. (but almost everyone had a gun!) |

Our exhibition begins with samplings of mid to late Victorian furniture which would have been found in late 1800s homes occupied by "families of means." The Queen Anne Chair (above) dates to the 1880s, and formerly resided in a Louisiana plantation home owned by the family of the museum's founder.

This Victorian couch is also from the living room of a Civil War Era Louisiana plantation

Victorian style chair from a noted 1800s New Orleans furniture builder

In the Victorian Era and the early years of the Industrial Age in America, running water and electricity had not yet entered the average home. In the "boudoir," it was not unusual to see a wash bowl and portable water pitcher. The Museum Of Yesterday has, as one of our permanent exhibits, a completely furnished and authentic Antebellum bedroom suite from a Louisiana plantation home. The oil lamp and wash stand shown above are part of that display which is known as the "Blue Room." All of the furnishings in this room, including the hand carved cherry wood bed, are from the Civil War era.

Marble and walnut dining room "breakfront" fixture was built in the era of the Civil War by a noted furniture maker in Atlanta. This piece survived the destruction of the Civil War. Before becoming part of the museum collection, it was previously housed in a plantation home in Edgard, Louisiana. By comparison, a similar piece, by the same builder, (photo below) dates to the year 1849 and presently graces the lobby of a restored historic hotel in Americus, Georgia.

This beautiful corner curio stand (above) was hand crafted in the early 1930's by the father of museum founder John DeMajo. It is based on a design that he recalled from a time when he and his family resided in Italy during his early childhood.

The image above is a 1940s vintage "smoker." At the end of World War - II, an estimated 42% of American adults regularly used tobacco products. In many typical mid-century homes, a smoking stand, such as the one above, would have been an expected piece of furniture right along with dad or mom's favorite easy chair.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE

20th CENTURY KITCHEN

20th CENTURY KITCHEN

|

No other room in the American home has undergone as many striking changes, as a result of technology and wartime innovation, as has the kitchen. War-time technology gave us a new direction in decorating with the use of extruded metals, including the generous use of aluminum and stainless-steel, more sophisticated electrical appliances, and most importantly, wide spread use of electric refrigeration. The photos below, illustrate the stark differences between a typical 1920s kitchen, a 1930s era kitchen (with indoor laundry facilities), and a kitchen of the Post-War era of the late 1940s. |

(Above) A typical kitchen of the early 1920's.

A 1930's kitchen. Note that in this era, laundry equipment began to find its way into the home.

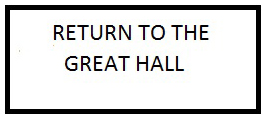

A late 1940's kitchen featuring Youngstown metal cabinetry and modern electric and gas appliances.

With the late 1940s development of modern appliances in the home, and the popularity of motion pictures, radio and television, many manufacturers tapped the talent pool of popular Radio, TV and screen actors to become spokesmen and women for their advertising campaigns. One such example was stage and screen actress Betty Furness who became the spokesperson for Westinghouse home appliances. Seen above is the Betty Furness home thermometer accessory kit intended to be used with Westinghouse home refrigerators and kitchen equipment. Other companies similarly called on popular talent such as competitor General Electric who selected actress Joan Davis as their kitchen spokesperson. Ms. Davis' popular 1950s TV series "I Married Joan" was sponsored by General Electric, and often featured Davis in the show's commercials.

During the 1950s technical revolution, manufacturers often used well known stage and screen personalities to promote their products. Above: Actress Betty Furness with Westinghouse refrigerator and comedian Joan Davis advertising competitor General Electric's kitchen appliances product.

In the pictures that follow, you will see some of the Museum of Yesterday's collection demonstrating the evolution of appliances and fixtures in the 20th Century American home kitchen and laundry.

Here we see an interesting contrast in styles between the chrome toaster, manufactured in 1932, and the Sunbeam coffee maker which immediately followed the end of World-War II. After the War, Americans began to appreciate the "sleek" lines of new kitchen appliances, many of which obtained their styling's from "high-tech" military images of the preceding years.

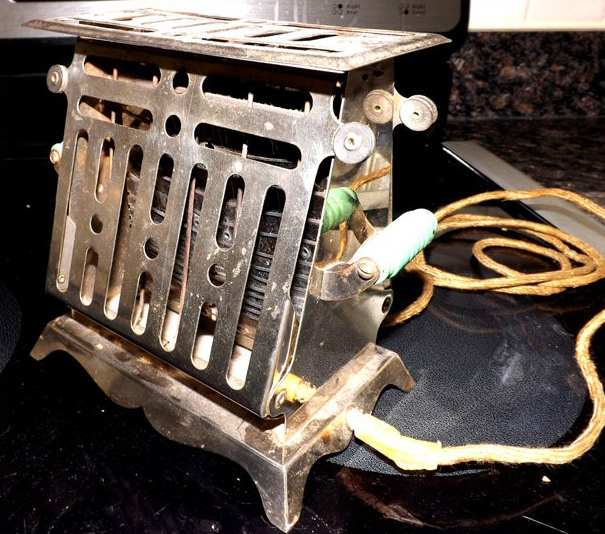

Another example of an early toaster. This Dominion Model 1 electric toaster, by Dominion Manufacturing Company of Minneapolis, MN, dates to the 1920s. The crudely engineered exposed electrical connections illustrate the absence of electrical safety standards in early home appliances, that we take for granted on modern appliances today.

In similar fashion, these 1930 hand operated kitchen utensils (egg beater, potato masher and meat grinder) sustained Americans during the Depression and WW-II years, but soon gave way to the electric "gadgets" that flooded the market immediately following the dark manufacturing years of 1941-1945.

In today's world of instant and freeze-dried coffee, many have forgotten that the preparation of a good cup of coffee was an art back in the early 20th Century. Home roasting of coffee beans, along with the familiar coffee mill to grind the roasted beans, was an every day prerequisite to the preparation of a pot of coffee. This ornate cast iron mill, which dates ca: 1900, is still capable of delivering the makings of a fantastic cup of java.

Life in "Middle America" during the early part of the 20th Century often involved the home processing of a family's food products, especially in the agricultural areas of the country. The item above is a wooden butter churn. Cream was skimmed from cow's milk and agitated in the churn to produce fresh butter.

Although we take air conditioning in the home for granted today, the average family of the mid-20th Century relied on electric fans, such as the one shown above, for cooling. This brass blade Emerson oscillating fan was the ultimate available solution for warm summer days and nights through the first half of the century. During that era, ceiling, pedestal or wall-mounted fans were the primary sources of cooling in churches, office buildings, and most public gathering places.

By the end of World War II, new homes were being built with large attic mounted fans that drew fresh air in through windows and exhausted hot air through the home's attic. It was not until the late 1950s that practical residential central air conditioning systems began to come on the scene.

NOSTALGIC COOKIE JARS FROM THE 1940'S

In the years just before and after World War-II, ceramic character cookie jars became a fad in American homes. These jars depicted a series of cartoon-like characters including bears, pigs, elves, and other story book like icons. Shown here is the Royal Ware Company 'bear" cookie jar which was popular during that era. Like many families in Post WW-II America, the DeMajo family had a Royal Ware bear cookie jar in their kitchen.

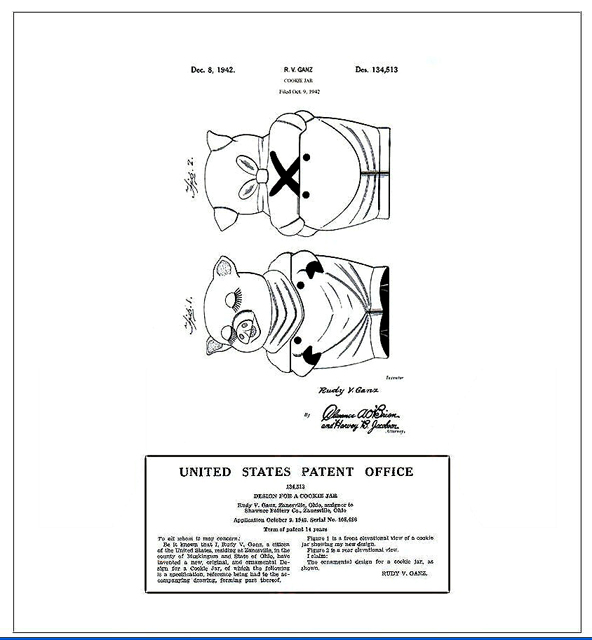

Below are additional examples of character ceramic cookie jars from the same era. These include the Shawnee "Smiley Pig" cookie jar, with Shawnee's patent design for these figures, and also a mint condition example of the "Chef Pig" character jar from Mercuries China. Today these nostalgic figures are highly sought after by baby boomers who had these popular items in their homes during that era.

The patent application for the Shawnee Smiley Pig design.

The production of "moonshine" alcohol was a common practice in America during the period known as Prohibition. Although Probation was later repealed, "moon shiners" continued to abound in many areas of the country. The jug shown above is but one of the home alcohol production implements in the museum's collection.

NOTE: The museum has acquired an actual copper moonshine still from a 1920's rural farm. The device is undergoing restoration and will be on display in the near future. We are planning to supplement that display with a demonstration of home brewing methods used then and today.

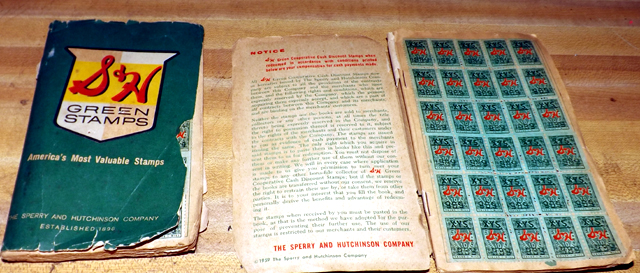

The 1950s saw a new innovation in shopping as the Sperry and Hurchinson Company introduced S&H Green Stamps. Joined later by the familiar yellow "Top Value Stamps," participating merchants were able to give their customers a universally accepted form of bonus for shopping at their stores. The number of stamps given was based on the price of the customer's purchase. Once the books were filled, they could be taken to a redemption center and redeemed to purchase merchandise offered by the redemption outlet. Later, as credit cards came into wide use, merchants discontinued the program due mainly to the imposition of fees imposed on them with the growing number of credit card transactions. Today, many credit card companies have replaced the S&H Green Stamp bonus concept with their own point system based on purchases made through the credit cards.

Coca-Cola and other carbonated drink products were extremely popular in the post WW-II era. These products had been rationed during the war so that a large portion of the stock could be sent to men and women in the Armed Forces overseas. Once the rationing was lifted, home consumption increased exponentially. This gave rise to home delivery services which supplied drinks directly to the home. The glass bottles carried a refund of around 2 cents in most states, which was instituted in order to keep the bottles from being added to landfills. In 1949, the redemption value of the case and bottles displayed above, would have been around 98 cents, proving that recycling is not a new concept. In fact soft drinks in glass bottles, with their inherent deposit, were more effective in the recycling effort than today's collection of aluminum cans and plastic water bottles which require reprocessing of materials rather than simple cleaning, sterilizing and refilling. Interestingly enough, the case of empty bottles, which once had a deposit value of under one-dollar, now sells for several hundred dollars as Coca-Cola memorabilia.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE

20th CENTURY HOME LAUNDRY

20th CENTURY HOME LAUNDRY

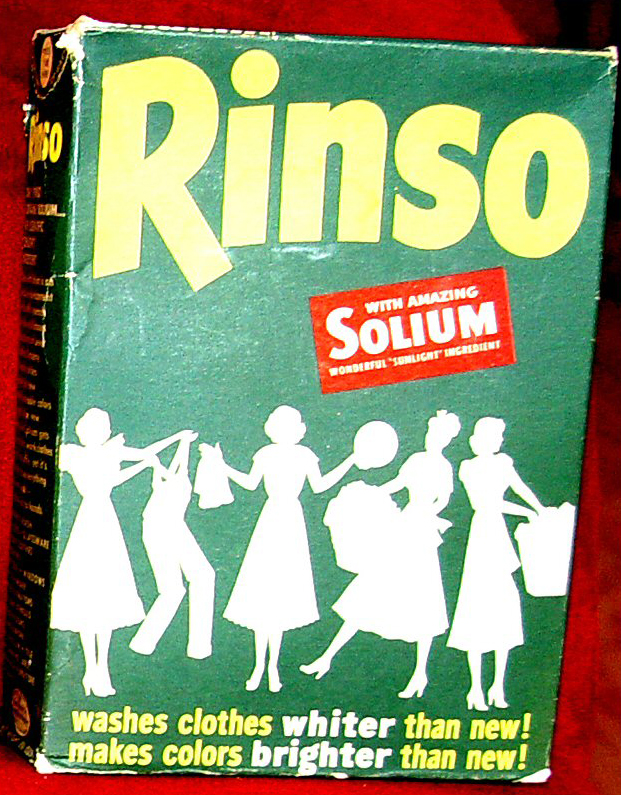

Click on the picture above to hear an actual 1940s and 50s radio commercial for "New Rinso with Solium"

Of course, "laundry day," in the "pre-Permanent Press"era of the 20th Century, involved starching and ironing clothes. This 1915 externally heated steam-and-dry iron would have been a regular fixture in any well appointed laundry room of that era. Early irons contained no internal heating element and, prior to each use, the iron had to be filled with water and then heated on a coal, oil or gas fired heating device.

The Clothes Pin was also a widely employed device in the home laundry prior to the advent of electric and gas dryers. These devices were used to secure wet clothes to an outdoor clothes line where they were air and sun dried.

SINGER "SPARTAN" MODEL PORTABLE SEWING MACHINE

|

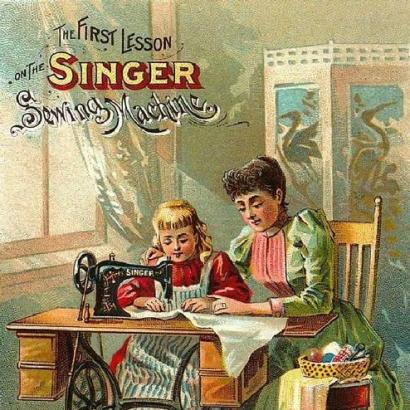

The invention of the sewing machine was another significant advancement that became popular in the American home during the early 20th Century. The first machines introduced were treadle operated. Later, the electric motor found its way into service on this appliance. While earlier machines were large cabinet mounted devices due to the support and mechanism required for treadle operation, the end of World-War II saw the introduction of the portable electric sewing machine. This Singer "Spartan" model, dating to 1959, is typical of earlier generation Singer portables. |

SINGER SEWING HISTORY-1950

Click the icon below to see the history of Singer Sewing Machines

The realities and rationing of the War, forced American families to find new ways of obtaining necessities such as clothing. This prompted many homemakers to spend time at their sewing machines in order to repair and recycle what cloth was available after military needs were met. .

After the War, the 1950’s saw a burgeoning love of technology. People now wanted the latest modern conveniences—and that applied to the fashion and garment industries as well. Sewing was no longer a household chore, and it became a creative outlet and a means of relaxation for many. During this decade, about 52 million women and girls sewed at home and bought over 90 million patterns a year. In 1956, the 1st SINGER brand “Grand Sew-Off” contest took place. The $125,000 contest was open to women across the nation enrolled in dressmaking at their local SINGER brand Sewing Centers. Thirty-three finalists flew to New York City where their garments were judged on fit and style: a true 1950s version of the fashion reality shows we see today!

PLUMBING IN THE HOME

|

In the first half of the 20th Century, hand pumps such as the one shown above, were a widely used means of supplying water to the home. These devices were usually installed near the kitchen sink on what was commonly called the "drain board," or else they were installed directly over a wellhead in the yard close to the home. Although there were several manufacturers, this cast iron model by Fairbanks-Morse was in wide use throughout the American landscape. |

MODERN LIGHTING IN THE HOME

From the 1800's on, improved lighting in the home began to develop. Initially, light was provided first by candle and then by oil or gas fired lamps. With the advent of the discovery and harnessing of electricity, the light fixture became an integral part of every room in the American home.

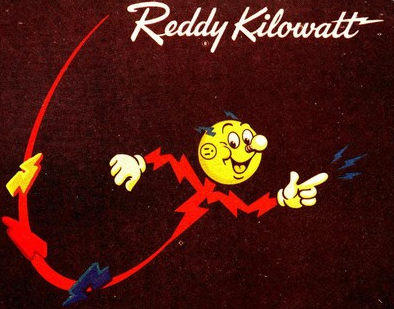

THE STORY OF REDDY KILOWATT

|

Easily recognizable to most people who were around in the years preceding 1980, the cartoon character Reddy Kilowatt became associated with electricity on the American landscape in 1926. As new electrical technology was taking hold, many independent power companies were formed in order to electrify the thousands of towns, cities, and rural segments of the country. As these companies emerged, there needed to be a common spokesman for the safe use of electricity in the home and work place. Reddy Kilowatt was that common bond between these energy providers. In the 1940s, cartoonist Walter Lance, creator of the Woody Woodpecker cartoon character, was responsible for taking Reddy to a new level of fame as his "recommendations for use of electricity" began to appear in theater previews, magazines and later on television. For those of us in the Baby Boomer generation, Reddy Kilowatt was with us for most of our young lives. |

The evolution of light in the home

Pictured are: kerosene lamp(1850's), Edison carbon filament "Mazda" lamp from 1900, standard GE incandescent bulb (1930's - 2012), the highly controversial compact fluorescent lamp which has proven to be a bigger hazard originally thought because of the danger of mercury contamination, the standard fluorescent lamp (1930's to present) a quartz-iodine lamp (right foreground) and the latest evolution, the Light Emitting Diode (2010) shown at left foreground. The standard incandescent lamp, which has served the world faithfully since the time of Thomas Edison, has now been rendered obsolete by the "green nut cases" that are running our government at the moment. It has been replaced by the "squiggly" compact fluorescent lamp which provides a certifiable "hazmat" incident anytime a lamp is broken or must be disposed of.

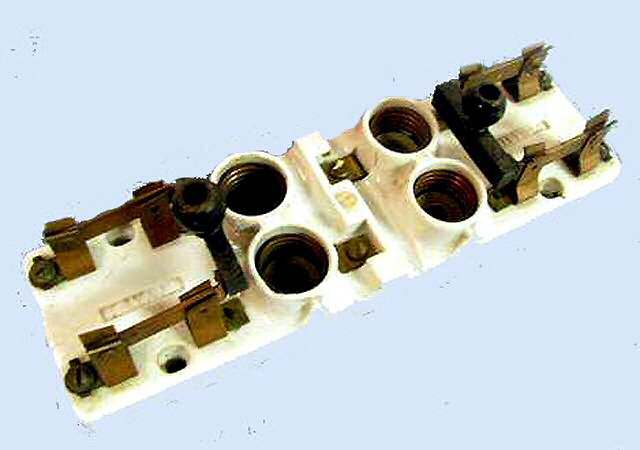

This lamp and fuse tester, which was manufactured by Royal Electric Company in the 1940-1955 era, was found in almost every hardware and department store where light bulbs and electrical accessories were sold. In that era, light bulbs, especially color coated 7-1/2 watt and 15 watt night light and decorative lighting bulbs, were often sold in open bins on the electrical supply counter. Variety stores such as S. H. Kress, F. W. Woolworth, along with most hardware and general stores, provided these test devices to allow customers to test unpackaged bulbs before purchasing them. If the bulb lit correctly in the presence of the store clerk, it was assumed that the bulb was good when the customer purchased it and left the store. By the mid 1960s, this type of tester was phased out because of the risk that someone could insert a finger or foreign object into the test sockets, thereby risking injury or danger of an electrical fire in the store. The museum is fortunate to have located a vintage Royal bulb tester for our permanent collection.

In the years prior to and during World War II, the safety of electrical devices in the home, and in commercial applications as well, was somewhat lacking by today's standards. Many homes and buildings that were wired in the infancy of electrification, utilized devices which had not yet born the test of time. As earth grounding of electrical distribution systems became the norm, the industry realized that there was danger from some of the older electrical systems which, by their very design, exposed people to the danger of accidental electrocution.

The over current protection device above, which could be found in many structures built in the 1900s-1930s, was a prime example. As the operator closed the knife switch by holding the black knob, the fingers came dangerously close to exposed and energized metal parts just below the handle. .

The Electrification of America by the Rural Electrification Administration

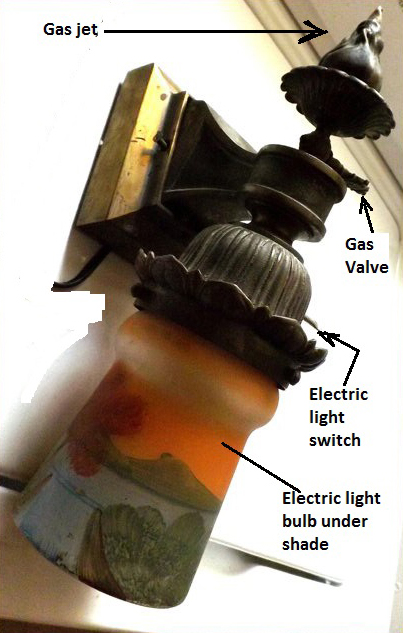

In most American cities, oil and gas lighting was still prevalent at the beginning of the 20th Century. In cities where electricity had been introduced, many homes were still being built with illuminating fixtures capable of using both electricity and natural gas. An example of these fixtures is shown below. By the late 1920s, electrification had taken hold in most localities. Often power was Direct Current, and was obtained by cooperatives that used power from electric street railways. In New Orleans, Louisiana, the city was traversed by a system of 600 volt street railway lines, and even into the later years of the 20th Century, many of the old buildings in the Central Business District still had evidence of DC powered lighting and elevators.

With the event of the Great Depression, the government made huge sums of money available, under the Works Progress Administration and various recovery programs, for electrification of areas of the country which had not enjoyed the development that many larger cities had. Common belief was that farms and rural homes and businesses could participate in the productive economy if they had access to affordable electricity. The REA (Rural Electrification Administration) was formed to assist in the utilization of power produced by large government power projects such as Hoover Dam, and to encourage the development of local power cooperatives that would ultimately provide the infrastructure to distribute power into areas where it was not economically feasible for large power producing corporations to run their distribution lines.

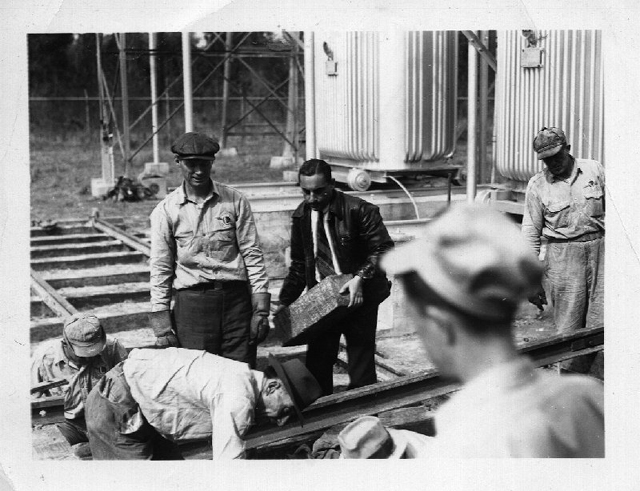

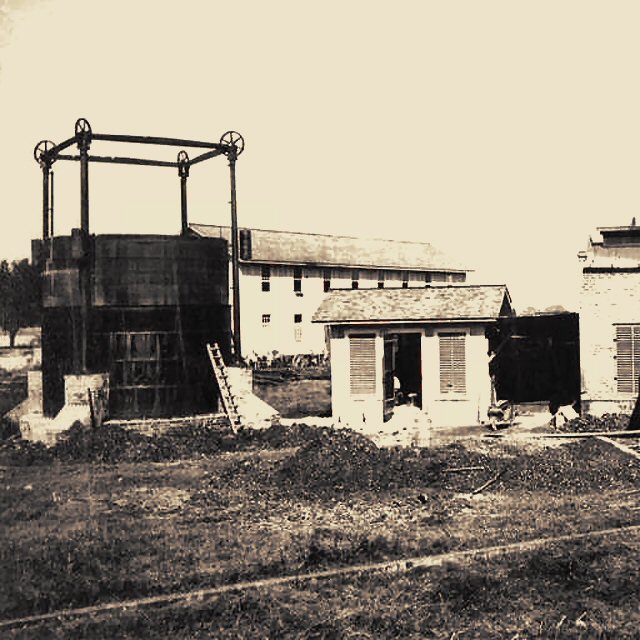

In the photo above, we see an actual local power company engineering crew in the process of constructing an electrical substation. The photo, which dates to 1939, shows these employees of the Louisiana Power And Light electrical cooperative, as they worked to bring power to rural Kenner, Louisiana. The supervising electrical engineer, wearing a suit and in the center of the photograph, is John R. DeMajo, father of Museum of Yesterday chairman John G. DeMajo. The activity depicted here, was typical of work being performed by REA crews across the nation during that era of government assisted expansion of the nation's electrical infrastructure.

In the photo above, we see an actual local power company engineering crew in the process of constructing an electrical substation. The photo, which dates to 1939, shows these employees of the Louisiana Power And Light electrical cooperative, as they worked to bring power to rural Kenner, Louisiana. The supervising electrical engineer, wearing a suit and in the center of the photograph, is John R. DeMajo, father of Museum of Yesterday chairman John G. DeMajo. The activity depicted here, was typical of work being performed by REA crews across the nation during that era of government assisted expansion of the nation's electrical infrastructure.

THE GAS LIGHT ERA OF THE LATE 19th CENTURY

Above: A combination electric/gas light fixture, dating to 1901, from a turn-of-the-Century home. Use of electricity was in its infancy at the time, and still somewhat undependable, so in the event of an electrical failure, the gas jet could be activated as a back-up source of lighting. The fixture was recovered during the renovation of a St. Charles Avenue mansion in New Orleans.

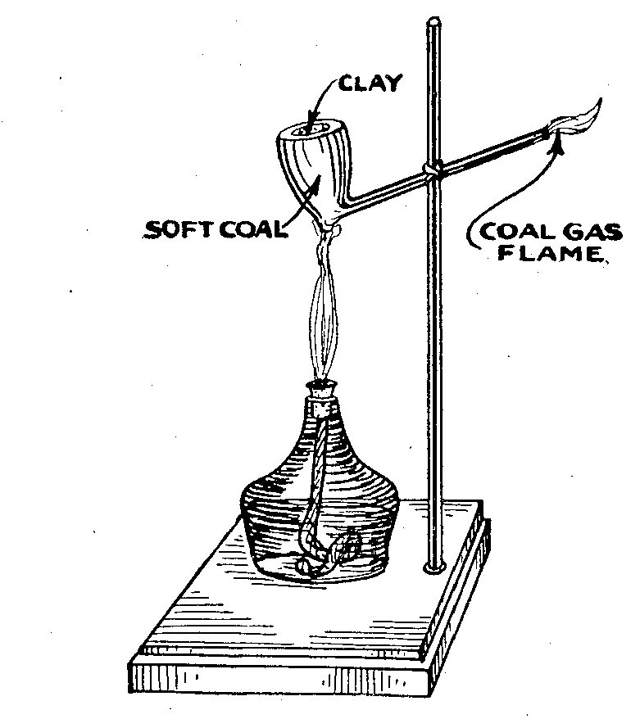

Another interesting note is that while natural gas in most of the country today is methane, a product of fossil fuel from wells drilled deep in the earth, in the early part of the last century, gas was obtained by burning coal and then recovering the unburned gas that was yielded from the center of the flames. In New Orleans, the gas plant of that era was located on what is now the corner of South Saratoga Street and Poydras Avenue.

Another interesting note is that while natural gas in most of the country today is methane, a product of fossil fuel from wells drilled deep in the earth, in the early part of the last century, gas was obtained by burning coal and then recovering the unburned gas that was yielded from the center of the flames. In New Orleans, the gas plant of that era was located on what is now the corner of South Saratoga Street and Poydras Avenue.

Above: an illustration showing how gas, for gas lighting and household use, was extracted from coal. Plants, employing this process, were built in cities all over the United States during the mid to late 1800s. Once produced, the gas was captured and piped into homes and businesses in the same manner as methane gas from wells is distributed today.

The photo below shows the municipal gas plant in New Orleans as it appeared during the Civil War. The plant was enlarged as the city grew, but it continued to occupy land on Poydras Street directly across from the present site of the Louisiana Superdome. When natural gas production, as a by-product of the oil industry, became widely accepted, New Orleans was switched to this new safer form of gas distribution. The remaining production equipment of the old Gas Works, was demolished in the 1940s.

While former President Obama led Americans to believe that he was the original promoter of Wind Power generated electricity, this 1937 catalog ad places things into more accurate perspective as it illustrates that wind turbines were widely accepted as a means of powering the rural American home well before "Barry" was around. Many homes and farms in the 1920s and 30s, depended on "off-the-grid" means of generating their own power. Self contained, automatic starting home generating plants, pioneered by the DELCO division of General Motors, were also widely used in areas where rural electrification by the R.E.A. and its various cooperatives had not yet become available. Battery powered "farm" radios also remained in wide use in many off-grid American homes during most of the Great Depression years.

By the time of the Civil War, the decorative oil lamp had become a well established accessory in the home. This iron parlor lamp from the 1850's is an example of lamps found in upscale homes of the era..

In the early 1900's, a wide range of lamp styles were available to the home decorator. This lamp shade, designed by Tiffany Studios of New York around 1905, was once part of the lighting in a large Esplanade Avenue home in New Orleans that our family once owned. It is a classic example of what was being done in that era with the employment of stained glass in lamps and fixtures.

A typical dual-bulb 1920's "parlor floor lamp" with leaded stained glass shade.

Desk lamps, such as this, were sold by electric utility companies under the description of "student desk lighting." The accompanying advertising slogan in many markets was part of a national campaign to promote electrical lighting products, and known as "Better light-better sight." Below is a typical industry ad promoting the "Better Light-Better Sight" program which existed from the mid 1930s well into the 1960s. Since these new modern lighting sources assured ample use of electrical power, most utility companies across the country signed on and perpetuated the ad campaign.

With the invention of the Edison Mazda lamp, lighting began to take on new and more convenient forms. This 1920's desk lamp, with reflecting hood, eased eye strain when the user was performing desktop work in an otherwise poorly lighted room.

A restored 1930's floor lamp is typical of the candelabra type floor lamps in millions of American homes during the Depression through the 1950's. These lamps were made of cast iron and pewter, and had a C7-1/2 watt night-light built in the base, as well as three flame bulb candlestick side lights at the top along with a Mogul base 3-way-200 watt bulb as the main illumination. The lamp shown above was completely sand blasted and restored to original condition and appearance in our own shop. The popular decor of that day usually included floral pattern lampshades. The shade shown here is a custom design by John DeMajo, and built by Lamp Emporium of Henrico, VA.

HOLIDAY LIGHTING AND DECORATIONS

from the DeMajo Family's two-hundred year-old Collection

from the DeMajo Family's two-hundred year-old Collection

For more than a century prior to electricity entering the home, illuminating the Christmas tree was a task for wax candles. Candle holders of many different designs and materials, were used to clip the candles to tree branches. The affluence of a family could often be told by the amount of precious metal contained in the family's candle holders that were passed down through generations. By the 1920s, many American families had disposed of their candle lighting in favor of safer and more ornate electric holiday lighting.

The scene above is an actual silver candle light holder on the Christmas tree at the Museum Of Yesterday's "Great Hall."

The early 1900s saw the introduction of Thomas Edison's light bulb in a form that was specifically intended for Christmas tree illumination. Just as was the case with Edison's early room illumination bulbs, these low voltage Edison lamps utilized carbon filaments and were intended for use on direct current electrical systems.

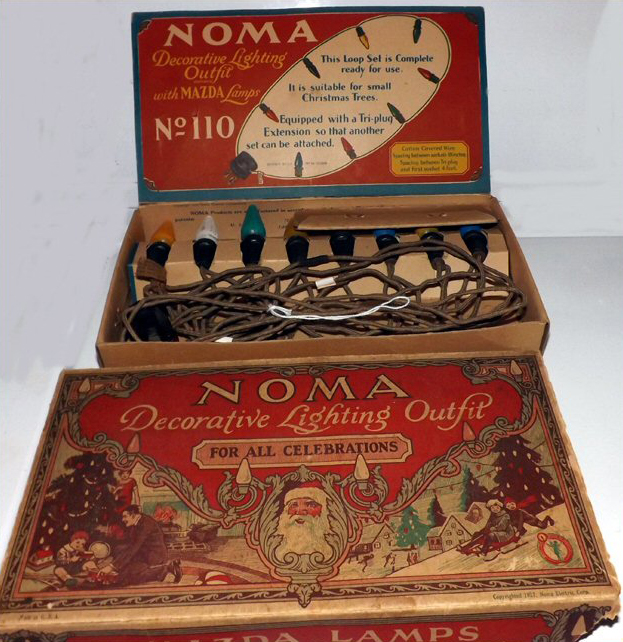

The NOMA lighting set shown above, is one of the first commercially sold lighting sets dating to 1927. It utilizes early exterior painted C6 lamps, and has the classic cotton/rubber wiring that was in use prior to the 1930s. The packaging also contains the very early NOMA graphic design. Note that the lamps are "Mazda" trademarked, which pre-dates the product to the later versions where the "Mazda" name was replaced by the General Electric trademark.

|

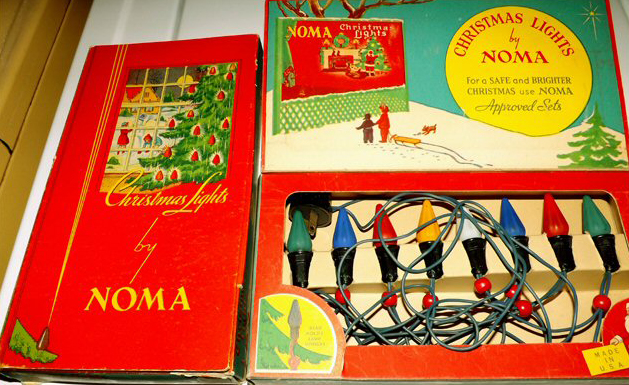

The museum has greatly enlarged our collection of antique Christmas and holiday lighting. We presently have over 100 different styles of antique Christmas lights ranging from 1900 through 1960. The collection includes an original Edison vacuum tip tree lighting bulb dating to circa 1911 (shown above). It was among the first commercially produced lamps that were specifically intended for holiday lighting purposes. The photos below show various assortments of bulbs and "bubble-lights" made between 1920 and 1960. Also displayed below are two typical "C" series lamp strings made by the NOMA company. During the mid-20th Century years, NOMA was the leading manufacturer of Christmas and holiday specialty lighting in the United States. "Bubble-Lights" became extremely popular in the 1940s and 50s. Alcohol, sealed in a glass tube, was heated by a small light bulb, which caused it to boil. Although most commonly associated with Christmas decorations, the artistic technology that enabled these lamps can be attributed to the Rudolph Wurlitzer Company and their "bubbling" juke boxes of that era. Shortly after World War II, a number of lighting manufacturers began creating figured light bulbs for use in standard C6 and C7 lighting strings. The collection contains examples of most of the figured bulbs that were available in the early 1950s. |

A complete sampling of holiday lighting spanning the period from 1902 to 1960.

The museum recently acquired this rare 1949 vintage bubble light. Although very popular at the time of their manufacture, mainly because the bulbs were easily replaceable, examples of these decorations are extremely scarce today. This is attributed to the fact that the plastic components were made with a high volatility plastic. When the C-7 lamp, housed inside of the decorative casing, became warm, the heat caused the plastic to slowly vaporize, resulting in misshapen and distorted housings. The above example, now on display at the museum, was never used, and therefore is in absolute mint condition.

Shown above is a selection of lights that would likely have been found on a pre1940s Christmas tree. The Edison Mazda bulbs were a color coated version of the Mazda lamps used in that era to light movie theater marquees, fair grounds lighting streamers, and other decorative applications. During this same era, the C7 lamp series became popular, first with the round bulbs shown above, and then with the flame tipped bulbs in the C6, C7 and C9 sizes. Later, General Electric took over the line of Christmas lighting bulbs from Mazda, with NOMA making the string and socket sets. Below are some post-war NOMA lighting sets. The familiar NOMA red and green boxes should be easily recognized by baby boomers.

Please continue your tour through the museum. By pressing the button below, you will be returned to the Great Hall where you will be able to select our other galleries and exhibits.

Copyright 2020 The Museum Of Yesterday, Chesterfield, VA USA